9 Neural Networks

9.1 Introduction

Many of the most impressive achievements in machine learning stem from the development of “artificial neural networks.” The earliest ideas for building algorithms based on models of neurons go back to the 1940s and peaked in the late 1950s and early 1960s with the development of the “perceptron,” an early example of what we now call a multi-layer neural net. Hardware limitations, along with a tendency to overstate the power of these early techniques, led to the abandonment of these ideas for nearly 50 years until Geoffrey Hinton and others returned to them, supported by dramatic improvements in computing power, specialized hardware such as GPUs, and several crucial advances in optimization algorithms. Since then neural networks have demonstrated an amazing ability to “learn” and have overcome challenges in image recognition and other classic problems in artificial intelligence, culminating in the invention of the attention mechanism, the transformer, and the modern LLM.

9.2 Basics of Neural Networks

At its heart, a neural network is a function \(F\) that is built out of two simple components:

- linear maps (matrices)

- simple non-linear maps (activation functions).

The function \(F\) is the composition of these types of functions so that \(F(x) = \cdots \sigma_2\circ M_2\circ\sigma_1\circ M_1\).

The structure of the different layers, the shape of the matrices \(M_{i}\), and the choice of non-linear transition functions make up the architecture of the neural network.

Suppose we want to build a neural network that recognizes pictures of cats. We begin with a large collection of images (a training set) \(x_i\) and labels \(y_i\) indicating whether \(x_i\) is a “cat” (1) or “not-cat” (0). Our goal is to learn a function \(F\) that assigns to each image a probability between \(0\) and \(1\) measuring how likely it is that the picture is a cat.

To do this, we choose an architecture for our neural network \(F\) and initialize its weight matrices randomly. Then we compute \(F(x_i)\) and compare it to \(y_i\). Using an optimization algorithm, we adjust the weights until \(F(x_i)\) is close to \(1\) when \(y_i = 1\) and close to \(0\) when \(y_i = 0\). Eventually, we obtain a function that, hopefully, can recognize images that were not in its training set, assigning high probabilities to pictures of cats and low probabilities to pictures of non-cats.

In fact, both linear and logistic regression fit into this framework and are very simple examples of neural networks. In the case of linear regression, we have training data \((x_i,y_i)\) and our goal is to find a matrix \(M\) so that the function \(Y=MX\) is a good approximation to the relationship \(y_i\approx Mx_i\). The error is measured by the mean squared error, and we can find \(M\) either analytically or by gradient descent. In this case the neural network is purely linear, with no nonlinear maps involved.

In the case of (simple) logistic regression, we have a collection of data \((x_i,y_i)\) where \(y_i\) is \(0\) or \(1\) and the \(x_i\) are vectors of length \(n\). Here we use the logistic function \(\sigma\) together with a weight vector \(w\in\mathbb{R}^n\) and consider \(F(x_i) = \sigma(w\cdot x_i)\). The error we measure is the negative log-likelihood of the data given the probabilities \(F(x_i)\), which works out to

\[ L = -\sum_i \big(y_{i}\log F(x_i) + (1-y_i)\log(1-F(x_i))\big) \]

and we find \(w\) by iteratively minimizing this \(L\).

9.3 Graphical Representation of Neural Networks

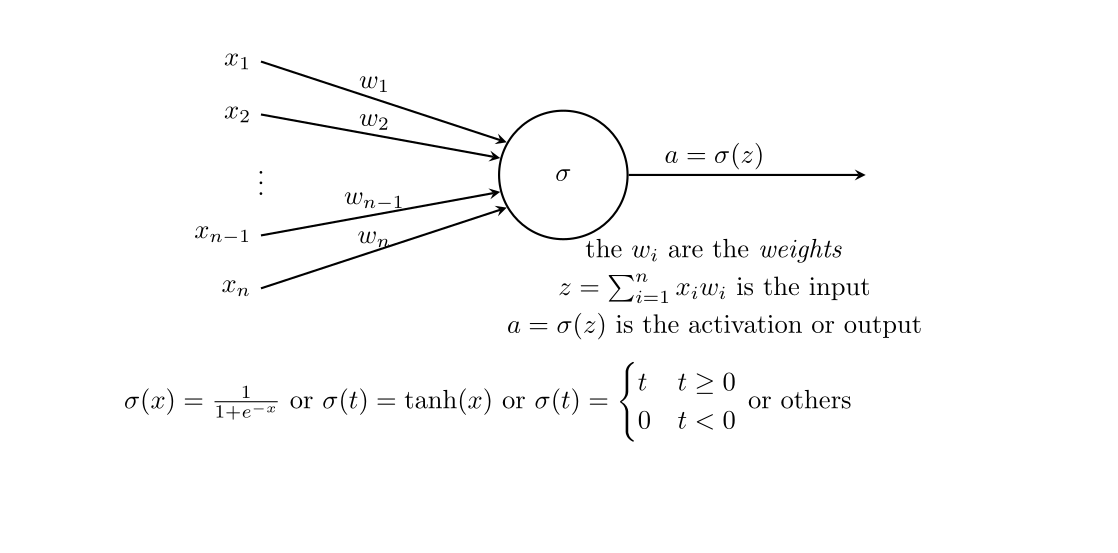

It is traditional, when working with neural networks, to take advantage of a graphical representation of the structure of the network. Figure 9.1 shows the fundamental element of such a graphical representation—a single “neuron.” Here, the inputs \(x_{i}\) flow into the neuron along the arrows from the left, where they are multiplied by the weights \(w_{i}\). Then these values \(x_{i}w_{i}\) are summed, yielding \(z=\sum_{i} x_{i}w_{i}\), and the nonlinear “activation” function \(\sigma\) is applied; the result is \(a=\sigma(z)\).

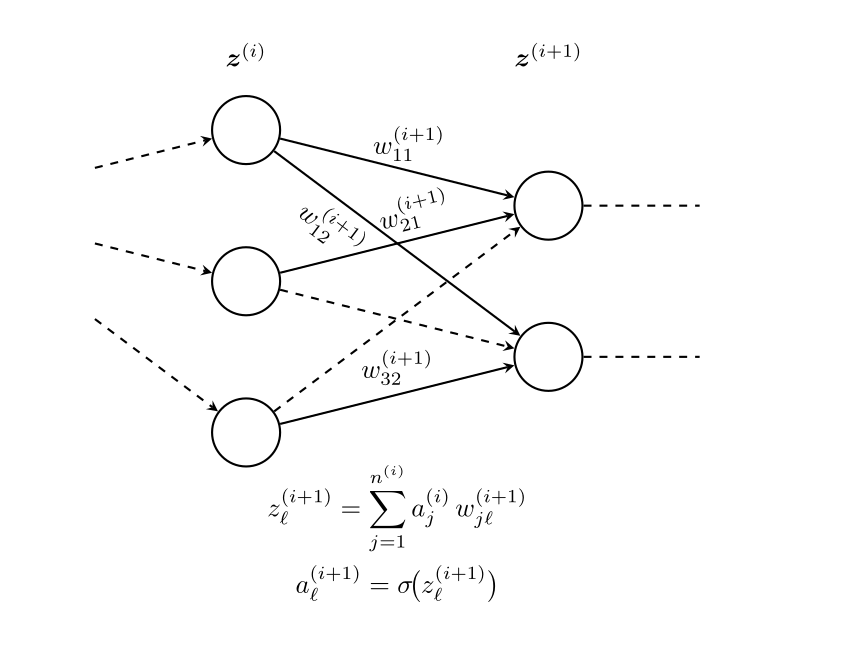

A full-fledged neural network is built up from “layers.” Each layer consists of a collection of neurons with input connections from the previous layer and output connections to the next layer. This structure is illustrated in Figure 9.2.

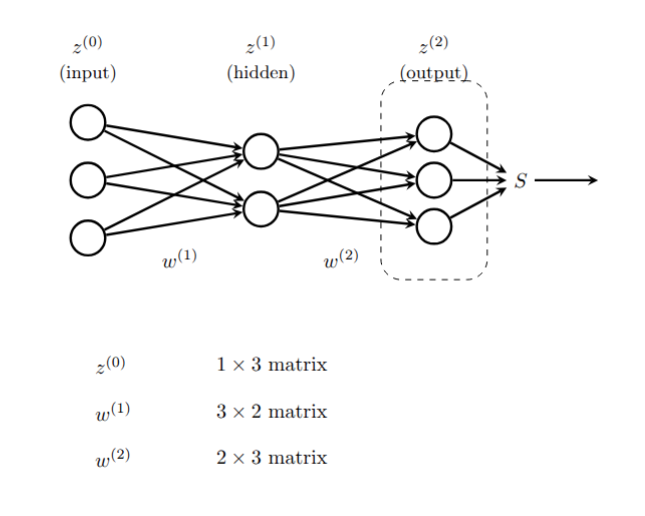

A multi-layer neural network with specified weights and activation functions defines a function called the “inference” or “feed-forward” function. Consider the simple example shown in Figure 9.3.

The input layer has 3 components, which we can represent as a \(1\times 3\) row vector with entries \((z_{1}^{(0)},z_{2}^{(0)},z_{3}^{(0)})\). The middle “hidden layer” has two nodes. The 6 weights \(w_{ij}^{(1)}\) connecting node \(z^{(0)}_{i}\) to \(z^{(1)}_{j}\) form a \(3\times 2\) matrix \(W^{(1)}\) where \[ z^{(1)}_{j} = \sum_{i=1}^{3} z^{(0)}_{i} w_{ij}^{(1)}. \]

The outputs of the hidden layer are obtained by applying the activation function \(\sigma\) to each of the \(z^{(1)}_{j}\): \[ a^{(1)}_{j} = \sigma(z^{(1)}_{j}) \] for \(j=1,2\). These activations are the inputs to the final layer, which has 3 nodes. The weights \(w_{jk}^{(2)}\) connecting the hidden layer to the output layer form a \(2\times 3\) matrix \(W^{(2)}\), where \[ z^{(2)}_{k} = \sum_{j=1}^{2} a^{(1)}_{j} w_{jk}^{(2)}. \]

The last step is to apply an output function to the vector \(z^{(2)}\). While activation functions are typically applied element-wise, the output function often uses all of the values in the layer.

Putting this together, the feed-forward function \(F\) looks like \[ F(z^{(0)}) = S(\sigma(z^{(0)}W^{(1)})W^{(2)}) \]

Here, the function \(\sigma\) is applied element-wise to the vector \(z^{(0)}W^{(1)}\), while the output function \(S\) is applied to the entire vector \(z^{(2)}\).

9.3.0.1 Linear Regression as a Neural Network

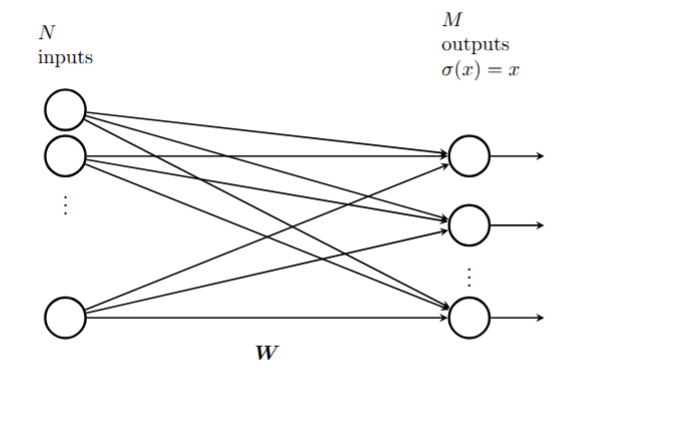

A simple linear regression problem takes an \(N\)-dimensional input vector \(x\) (which we write as a \(1\times N\) row vector) and produces an \(M\)-dimensional output vector \(y\) (which we write as a \(1\times M\) row vector) by multiplying by a weight matrix \(W\) so that \(y=xW\).

This is a neural network with no activation function, just a single layer with weight matrix \(W\) and the identity as the output function.

9.3.0.2 Logistic Regression as a Neural Network

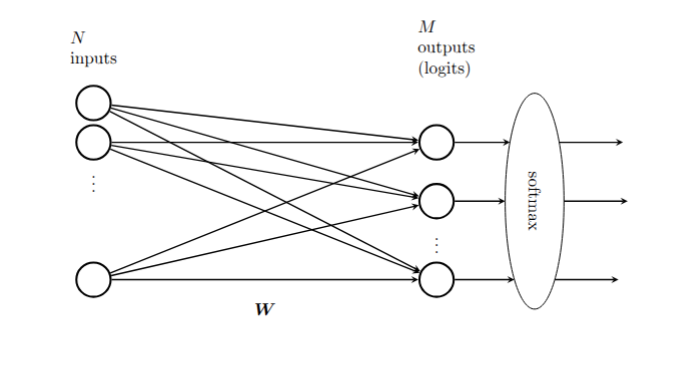

While linear regression can be represented as a trivial neural network, logistic regression is a more interesting example. Consider the problem of multi-class logistic regression, where the input vector is an \(N\)-dimensional row vector \(x\) and the output is a probability distribution over \(M\) classes, represented as an \(M\)-dimensional row vector \(y\) with non-negative entries summing to one.

From our earlier work, we know that this model relies on an \(N\times M\) weight matrix, and the output of the logistic model is \(F(x) = S(xW)\), where \(S\) is the softmax function defined by \[ S(z)_{i} = \frac{e^{z_{i}}}{\sum_{j=1}^{M} e^{z_{j}}}. \]

The graphical representation of this neural network is shown in Figure 9.5.

9.4 Loss functions and training

Given a large collection of data \((x^{[i]},y^{[i]})\), where \(x\) is the input and \(y\) the target output, the goal of training a neural network \(F_{W}\) on this data is to adjust the weights \(W\) in \(F_{W}\) so that \(F(x^{[i]})\) is “approximately” \(y^{[i]}\). To make sense of this, we need to quantify how close \(F(x^{[i]})\) is to \(y^{[i]}\) by means of a function \(L_{W}\) called the “loss function.”

The choice of a loss function is based on the ultimate purpose of the neural network. We have seen two widely used examples. The first, which arises in linear regression, is the “mean squared error”. On a single data point \((x^{[i]},y^{[i]})\), this loss function is

\[ L_{W}(F_{W}(x^{[i]}),y^{[i]}) = \|F_{W}(x^{[i]})-y^{[i]}\|^2 \]

and the overall loss is

\[ L_{W}=\frac{1}{M}\sum_{i=1}^{M} \|F_{W}(x^{[i]})-y^{[i]}\|^2. \]

In the case of multi-class classification (with, say, \(n\) classes), the loss function is usually the “cross entropy”. In this case the output vectors \(y^{[i]}\) are \((y_{1}^{[i]},\ldots, y_{n}^{[i]})\) where the \(y_j^{[i]}\) are all zero except for a \(1\) in the \(j\)th position where the proper class assignment is class \(j\). (This is called one-hot encoding). The output layer of a classification network consists of \((z_{1},\ldots, z_{n})\) which are passed through the softmax function yielding \[ (\frac{e^{z_1}}{H},\ldots, \frac{e^{z_{n}}}{H}) \] where \(H=\sum_{j=1}^{n} e^{z_{j}}.\) If we write \(p_{j}=e^{z_{j}}/H\), then the loss for a single data point \((x^{[i]},y^{[i]})\) is

\[ L_{W}(x^{[i]},y^{[i]}) = -\sum_{j=1}^{n} y^{[i]}_{j}\log(p_{j}) \]

and the total loss would be

\[ L_{W} = \frac{1}{M}\sum_{i=1}^{M} L_{W}(x^{[i]},y^{[i]}) \]

It is important to recognize that the loss is a function of the weights of the network; the data \((x,y)\) are fixed.

The goal of training is to minimize \(L_{W}\) by varying \(W\). From a mathematical point of view, we do this by gradient descent. That is to say, for the fixed collection of data, we iteratively calculate \(\partial L_{W}/\partial W^{(j)}_{kl}\) for all the weights \(W^{(j)}_{kl}\) in the network, and then make a small adjustment \[ W^{(j)}_{kl} = W^{(j)}_{kl} - \lambda \frac{\partial L_{W}}{\partial W^{(j)}_{kl}} \] until the loss function changes by less than some threshold amount on each iteration.

Computing the partial derivatives \(\partial L_{W}/\partial W^{(j)}_{kl}\) is a miraculous application of the chain rule that exploits the architecture of the neural network. The algorithm for this computation is called “backpropagation” and we will discuss it in the next section.

9.5 Backpropagation

Our neural network is made up of \(n\) layers, with the output of the final \(n\)th layer serving as input to the loss function. The nodes at the \(j\)th layer have values \(z^{(j)}_{k}\). The idea behind backpropagation is, for each data point \((x^{[i]},y^{[i]})\), to compute vectors \[ \delta^{(j)}_{k} = \frac{\partial L_{W}}{\partial z^{(j)}_{k}} \] inductively starting with \(j=n\) and working backwards. From these \(\delta^{(j)}\) we can then compute the partials \(\partial L_{W}/\partial W^{(j)}_{rs}\).

Since the total loss is accumulated as a sum over the data points, we can sum the \(\delta^{(j)}_{k}\) obtained from successive data points to compute the gradient of the loss over all the data or over some portion of the data, and use these accumulated gradients to adjust the weights.

The term “backpropagation” comes from the fact that we compute the \(\delta\) starting at the output end of the network and working backwards toward the input end, in contrast with the inference or forward pass which goes from the input to the output.

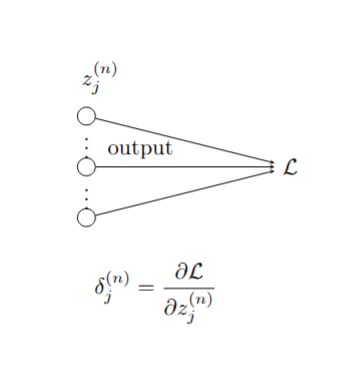

9.5.1 Backpropagation: first step

The first step of the backpropagation algorithm comes from the output layer of the neural network. The elements of the last layer \(z^{(n)}\) are fed directly into the loss function \(L_{W}\) as shown in Figure 9.6. Therefore, \[ \delta^{(n)}_j = \frac{\partial L_{W}}{\partial z^{(n)}_{j}} \] depends on the loss function \(L_{W}\). Let’s look at the two cases we considered above separately.

9.5.1.1 Mean Squared Error

In this case, as we’ve seen, the loss function is given by the squared Euclidean distance between the output vector \(z^{(n)}\) and the target vector \(y^{[i]}\). \[ L_{W}(x^{[i]},y^{[i]}) = \|z^{(n)}-y^{[i]}\|^2 \] and therefore the derivative is just \[ \frac{\partial L_{W}}{\partial z^{(n)}_{j}} = 2(z_{j}^{(n)}-y_{j}^{[i]}). \]

In other words, since we are going to adjust the scaling anyway when we do gradient descent, we can set \[ \delta^{(n)} = z^{(n)}-y^{[i]}. \]

9.5.1.2 Cross Entropy

In the classification problem we saw that \[ L_{W}(x^{[i]},y^{[i]}) = -\sum y^{[i]}_{j}\log\frac{e^{z^{(n)_{j}}}}{H} \] where \(H=\sum_{j} e^{z^{(n)}_{j}}\). Therefore \[ \delta^{(n)}_{j} = \frac{\partial L_{W}}{\partial z_{j}^{(n)}} = -y^{[i]}_{j}+\frac{\partial \log H}{\partial z_{j}^{(n)}} \] which gives \[ \delta^{(n)}_{j} = -y_{j}^{[i]}+p_{j} \] where \[ p_{j}=\frac{e^{z_{j}^{(n)}}}{H} \]

Putting this together yields \[ \delta^{(n)} = -y^{[i]}+p \] where \(p\) is the vector of probabilities with entries \(p_{j} = e^{z^{(n)}_{j}}/H\).

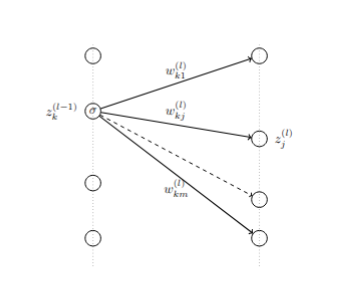

9.5.2 Backpropagation - inductive steps

To continue the backpropagation steps, we are going to compute \(\delta^{(i-1)}\) from \(\delta^{(i)}\) for \(i<n\) inductively. Again, the key is the chain rule: \[ \delta^{(i-1)}_k = \frac{\partial L_{W}}{\partial z^{(i-1)}_{k}} = \sum_{t}\frac{\partial L_{W}}{\partial z^{(i)}_{t}}\frac{\partial z^{(i)}_{t}}{\partial z^{(i-1)}_{k}} \]

The structure of the neural network tells us that \[ z_{t}^{(i)} = \sum_{j} \sigma(z_{j}^{(i-1)})w_{jt}^{(i)}. \tag{9.1}\]

Therefore \[ \frac{\partial z^{(i)}_{t}}{\partial z^{(i-1)}_{k}}= \sigma'(z_{k}^{(i-1)})w_{kt}^{(i)}. \]

Putting this in the chain rule sum yields \[ \frac{\partial L_{W}}{\partial z^{(i-1)}_{k}} = \sum_{t}\frac{\partial L_{W}}{\partial z^{(i)}_{t}}\sigma'(z_{k}^{(i-1)})w_{kt}^{(i)}. \]

In other words \[ \delta^{(i-1)}_{k} = \sigma'(z_{k}^{(i-1)})w_{kt}^{(i)}\delta^{(i)}_{t} \] or, in vector form,

\[ \delta^{(i-1)} = \sigma'(z^{(i-1)})W^{(i)}\delta^{(i)} \] where the multiplication by the vector \((\sigma'(z^{(i-1)}_{j}))\) is done componentwise.

9.5.3 Backpropagation - putting it together

As we’ve seen, by a backward pass through the network we can compute the \(\delta^{(i)}\), which are essentially the gradients of \(L_{W}\) with respect to the variables making up the \(i\)th layer.

Of course, what we really want are the gradients with respect to the weights, and that requires one more use of the chain rule. We see that \[ \frac{\partial L_{W}}{\partial w^{(i)}_{jk}} = \sum \frac{\partial L_{W}}{\partial z^{(i)}_{k}}\frac{\partial z^{(i)}_{k}}{\partial w^{(i)}_{jk}} \] and from Equation 9.1 we have

\[ \frac{\partial z^{(i)}_{k}}{\partial w^{(i)}_{jk}} = \sigma(z^{(i-1)}_{j}). \]

As a result, \[ \frac{\partial L_{W}}{\partial w^{(i)}_{jk}} = \delta^{(i)}_{k}\sigma(z^{(i-1)}_{j}). \]

The gradient \(\nabla W^{(i)}\) of \(W^{(i)}\) is therefore a matrix whose \(jk\) entry is given by \[ \frac{\partial L_{W}}{\partial w^{(i)}_{jk}}=\sigma(z^{(i-1)}_{j})\delta^{(i)}_{k}. \] This is sometimes called the outer product of the vectors \(\sigma(z^{(i-1)})\) and \(\delta^{(i)}\) or just the matrix product of the column vector \(\delta^{(i)}\) and the row vector \(\sigma(z^{(i-1)})\) (in that order).

9.5.4 Training

The training process for a neural network uses successive forward (inference) passes and backward (backpropagation) passes to iteratively move the weights of the network in a way that reduces the loss function.

More specifically, begin by setting all the \(\delta^{(i)}\) and \(\nabla W^{(i)}\) to zero, and initialize the weights of the network randomly. Then, for each \((x,y)\) in the dataset:

make a forward pass through the network, computing and saving the inputs \(z^{(i)}\) for each layer.

make a backward pass through the network, computing the \(\delta^{(i)}\) and the \(\nabla W^{(i)}\) at each layer using the backpropagation formulae. Accumulate the \(\delta^{(i)}\) and \(\nabla W^{(i)}\) from each pass into variables \(\delta^{(i)}_{*}\) and \(\nabla W^{(i)}_{*}\).

periodically (after each iteration, after a fixed number of data points, or after a complete pass through the data), update the weights using your chosen version of gradient descent; the simplest approach is: \[ W^{(i)} \leftarrow W^{(i)}-\lambda \nabla W^{(i)}_{*} \] for a learning rate \(\lambda\). Then reset all of the accumulators \(\delta^{(i)}_{*}\) and \(\nabla W^{(i)}_{*}\) to zero.

Once every data point in the dataset has been considered, you have completed one training epoch. Repeat until the loss stops decreasing meaningfully.